LWF_RetrofitGuide_Accessible_for_Web

October 16, 2022 – By Meghan Snow – Seeing a forest recently burned in a wildfire can be jarring. Green is replaced by shades of gray. The land is quiet. The sunshine feels hotter. However, it’s not long before the forest comes back to life.

“Wildlife is incredibly resilient,” said Stephanie Eyes, a senior wildlife biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office. “California has a long history with wildfire, and many species adapted to endure it.”

Eyes has evaluated the impacts of wildfire on wildlife for more than a decade. Before joining the Service, she worked for Yosemite National Park, surveying the impacts of fire on California spotted owl. Today, she uses data collected on wildfires to determine the impact on habitat for endangered, threatened and at-risk species living in the Sierra Nevada.

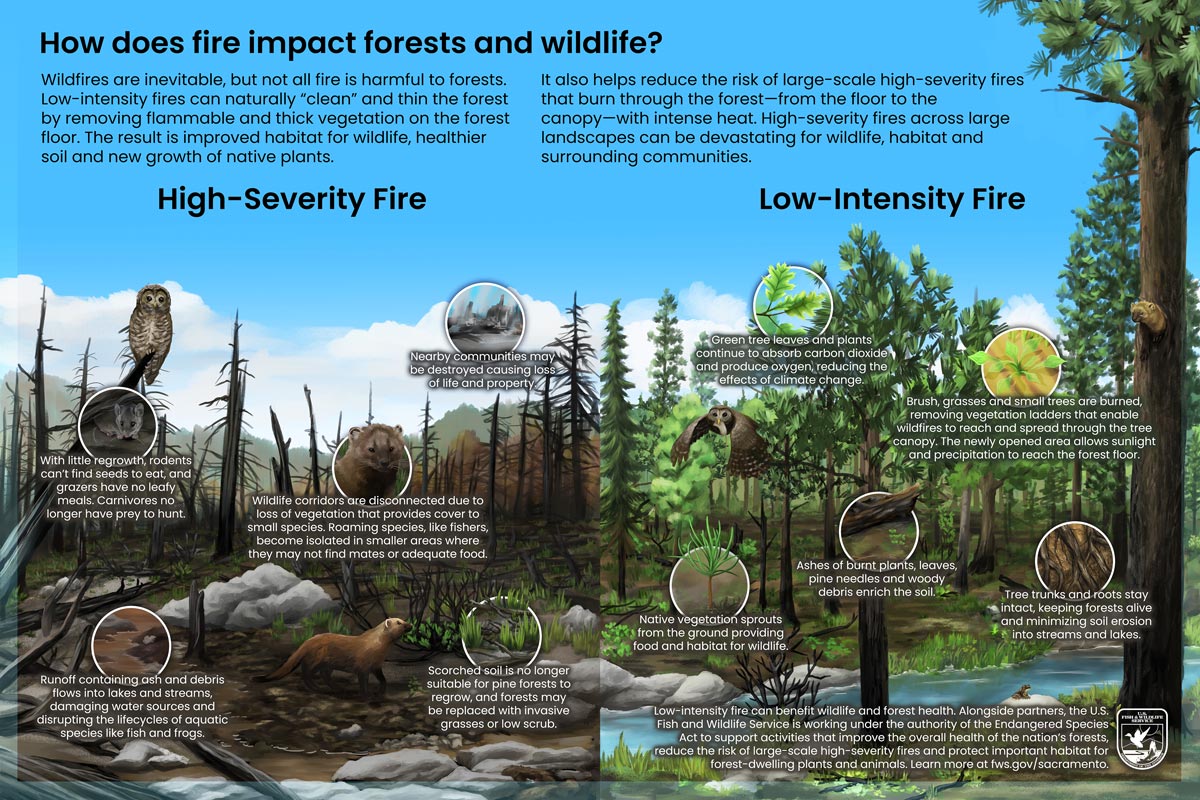

Fires burn at different heat levels, can be large or small, and cause varying impacts on the land, wildlife, and nearby communities. Topography, the amount of dry vegetation present and weather factor into how large and damaging the fire becomes. Low-intensity fires burn close to the ground, “cleaning” and thinning the forest by removing thick and flammable vegetation from the forest floor. High-severity fires burn with high heat, climb into and remove the tree canopy, and can scorch the soil and tree roots. At a large scale, high-severity fires can be incredibly damaging to wildlife and the ecosystem. Mosaic fires are a mix of mostly low-intensity fire with patches of high- and moderate-severity fire and some unburned forest. Wildlife can survive, and even thrive, in areas that experience mosaic fires.

When wildfires erupt, animals do their best to move out of the direct path of the flames while staying close to home if they can find safe refuge.

“Wildlife will move around their home area, avoiding the smoke and actively burning areas until it’s safe to return,” explained Eyes.

Some animals, like frogs and rodents, don’t move far. They’ll retreat into deep underground burrows where they are protected from the heat. Fish and frogs will swim to the deepest parts of their stream or lake. If the fire is burning just a few feet high, birds and animals that can climb will sometimes go up into the branches and tree canopy to avoid the flames. Fishers may crawl into a tree cavity for protection. Other animals, like deer and bears, will move around the forest until the flames subside.

“When I was working in Yosemite, there was a female California spotted owl who weathered several wildfires. We were always concerned about her, but she would still be there, year-after-year,” said Eyes.

But when a high-severity fire burns across a large landscape, it moves fast and climbs through the tree canopy. Wildlife has a more challenging time finding refuge from these flames.

“Wildlife have adapted to deal with smaller fires, and unfortunately, sometimes they can’t escape these recent, big fires,” said Eyes.

The Service listed the southern Sierra Nevada fisher in 2019 and the Sierra Nevada red fox in 2021, both as endangered species. High-severity wildfires were identified among the leading threats to the ongoing survival of both species due to loss of habitat and elimination of safe movement corridors. As climate change prolongs periods of drought, forests and the species that live there will continue to face the threat of large, high-severity wildfires.

AFTER THE BURN

Over the past seven years, high-severity wildfires burned thousands of acres across California. Unprecedented drought mixed with mid-summer lightning storms ignited wildfires so large they created their own weather systems. While many areas burned severely, pockets of forest continue to thrive.

Nancy Kelly, a wildlife biologist for the U.S. Forest Service’s Sequoia National Forest, has worked for more than 20 years surveying and studying wildlife habitat.

“The adaptability of wildlife continues to surprise me,” said Kelly. “They can make do with what’s left after a fire.”

As a wildlife biologist, Kelly advises staff at Sequoia National Forest on ways to reduce the impact of management activities, such as prescribed burns and tree thinning projects, on endangered, threatened and at-risk species.

“Initially, fire is a big deal. It changes how species interact with their habitat for a long time,” said Kelly. “But fire is a tool that nature has been using for eons to keep ecosystems intact.”

After low-intensity fires, grasses and ferns are the first to come back, aided by newly enriched soil from the ashes of burned leaves, plants, and woody debris, as well as sunlight that can now reach the forest floor. Trees are still alive and sprout new leaves during the next growing season. Their intact root systems prevent soil from eroding into nearby streams and lakes.

“We have seen populations of sensitive plants double after a fire because they like the open canopy,” said Kelly.

It doesn’t take long for wildlife to start using low-intensity burn areas. New grasses, ferns and fallen branches provide just enough coverage for mice and squirrels to feel safe as they scavenge for seeds dropped during the fire. Their presence attracts owls, fishers, foxes and other animals that take advantage of newly opened areas on the forest floor to spot prey. Tender grass shoots provide food for herbivores like deer and rabbits. Amphibians scramble back to their waterfront homes to feast on insects that have also returned.

“We will see wildlife come back through the area as it cools back down,” said Kelly. “They’re curious like we are. They take advantage of the new growth and other food sources that are available after the burn.”

Regrowth after a large-scale, high-severity fire looks different. Some of the soil is scorched to a degree that tree roots underneath the surface are burned, killing the tree. Ash from leaves and woody debris may take longer to breakdown and enrich the soil to a point that vegetation can sprout from the ground. Rain can often cause the soil to erode into nearby waterways. Muddy waters result in less clean water sources for animals to drink from and can also bury amphibian and fish eggs before they hatch.

“While these high-severity burn areas look like moonscapes, they are not completely devoid of life. It’s just different life,” explained Kelly.

Woodboring beetles start colonizing the freshly burnt trees. Woodpeckers move in to eat the beetles. The dead trees fall, their ash providing much needed nutrients to restore the soil.

“Unfortunately, in some of these large, high-severity burns, we’re seeing more invasive grasses and weeds grow because they can survive in less ideal conditions,” said Kelly. “These species can outcompete native grasses and plants for water and light.”

One native plant, mountain white thorn, grows low to the ground when forest canopies are present. But after a high-severity fire, the shrub can regrow to heights over 6 feet. Their growth then blocks sunlight to tree seedlings sprouting from the ground, and the landscape can transition from forestland to scrubland.

Kelly explained that sometimes the animal life after a fire transitions, too.

“This year, we’ve seen red-tailed hawks and other grassland bird species because we have more open area now,” she said. “Until trees come back, I expect that we’ll continue to see these grassland and open area species in the mountains.”

TO STAY OR GO

More than 100 years could pass before large trees return to the landscape after a high-severity fire, and some species can’t survive without the forest canopy, even if they try.

“California spotted owls can find places to perch, but they can’t find good places for nesting,” said Eyes. “Just like us, if they don’t have a roof over their heads, they’ll leave.”

Fishers also avoid the open landscapes, which leave them vulnerable to predators as they move between their dens and scavenging grounds. Fishers often travel miles looking for food, mates and good reproductive habitat, but high-severity wildfires can often cut off those safe travel corridors, restricting them to smaller and smaller ranges and reducing their chances of finding a mate and enough prey.

Luckily, agencies like the U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management work to restore habitat after large fires like these.

“If a prescribed burn can be used to reduce the risk of a high-severity fire or vegetation can be planted immediately after the fire, the wildlife will typically come back,” said Eyes.

The Sequoia National Forest conducts a variety of activities aimed at reducing the risk of large-scale, high-severity fire, such as prescribed burns, brush management projects and thinning overgrown groves of trees. Kelly works with biologists at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to determine ways to minimize the impact on listed species in the area. While the projects cause some minor disruption while they’re taking place, the period is usually short and much less disruptive and damaging than a high-severity fire.

Kelly and her team also support the restoration of burned landscapes by replanting native vegetation and trees on open slopes and near streams to reduce erosion and jump start the process of bringing the area back to life.

“The forests provide the food, water and shelter for wildlife, but they’re also important to humans,” said Kelly. “By taking care of the forests, we’re also taking care of our air, water sources and communities.”

Source: USFWS

Brad Graevs of the Plumas Underburn Cooperative uses a drip torch to set fire to vegetation in Humboldt County as part of a controlled fire in June organized by the Humboldt County Prescribed Fire Association. Photo/Lenya Quinn-Davidson

Controlled burning has proven effective at reducing wildfire risks, but a lack of insurance has dissuaded private landowners from implementing the practice. Policy expert Michael Wara discusses soon-to-be-enacted legislation that would pay for fire damages to neighboring properties in California.

September 27, 2022 – By Rob Jordan,Stanford Woods Institute for the Environmen – Ironically, after California’s deadliest and most destructive wildfire season ever – in 2018 – insurance companies stopped providing coverage for one of the most promising ways to prevent such catastrophes.

To slow the scourge of wildfires, California needs controlled or prescribed burning of tinder-dry trees and brush known to fuel runaway wildfires – or vegetation thinning on about 20 million acres or nearly 20% of the state’s land area. Although more than 50% of the state’s land belongs to private owners, they have largely avoided prescribed burning in part due to fears of bankruptcy, according to previous Stanford University research. To assuage those fears, Stanford legal research scholar Michael Wara, in partnership with The Nature Conservancy and University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources fire advisors, assisted California state Sen. Bill Dodd in the development of legislation that would implement a $20 million fund to pay for prescribed fire damages to neighboring properties through 2028. The bill – SB 926 – received almost unanimous support from the state legislature, and awaits Gov. Gavin Newsom’s signature before it is finalized.

Below, Wara, director of the Climate and Energy Policy Program at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, discusses how to restart the insurance market for prescribed burning on private land, dispel misconceptions about the practice, and surmount related obstacles.

This past April, mistakes in a routine U.S. Forest Service prescribed burn led to New Mexico’s largest wildfire ever. What impact will that have on prescribed burning in California going forward?

CalFire – the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection – is a bit more anxious about prescribed fire than perhaps they were before New Mexico. But there are many different flavors of prescribed fire. SB 926 helps private landowners with smaller fires than what escaped in New Mexico. That fire was supposed to be 2,500 acres. Most prescribed burns on private land are about 10 acres, so there’s a lot less potential for damage. But there are far more of them conducted – more than 400 over the past few years – than is typical for the forest service.

Is the insurance industry’s risk aversion for prescribed burnings justified?

Based on our analysis over the past three years, only two out of 400 prescribed burns on private property in California have escaped. And when you say “escaped,” it doesn’t necessarily mean damages. They burned a little more than planned. A cattle grate was damaged in one case. The risk is really low, at least as far as we can tell from the actual data. CalFire has had two escapes in the past three years that did more damage and required more attention, but again, that’s a different beast from burns on private property.

What can be done to encourage insurers to issue policies for prescribed burn coverage?

Writing or issuing commercial fire insurance and reinsurance is not how you get promoted in the insurance industry. We need to change that. Lenya Quinn-Davidson of University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources and I are trying to build a much more comprehensive assessment of what the risk actually is. Bringing insurers into the market requires actuarial analysis. We want to replace preconceived notions and fears with data. Maybe you won’t sell me an insurance policy that covers that first loss, but maybe you would sell me one that covers loss above some very high deductible – maybe $2 million – because those losses are unlikely to occur.

Is a $20 million liability fund that only covers private land enough to make a dent in the massive amount of prescribed burning California needs to do?

This bill is a pilot. It’s intended to see what happens, see what we can learn. This is a targeted, surgical intervention to help a particular set of people who we think could play an important role in reducing risk. I think of them as the Good Samaritans of fire. They are going out on their weekends, getting paid nominal money if anything, and working to make their communities safer. How to better manage private lands for fire risk in California is a huge issue. The odds these parcels are important go up as you get closer to communities. A lot of this is aimed at protecting small-town California. These places where there’s a lot of risk, you’ve also got lots of private landowners.

Some people are concerned by the prospect of frequent, purposefully set fires. What can be done to reassure them?

The way public opinion on prescribed fire changes is with engagement. Community meetings, personal experience, and accurate depictions in trusted media are key. In general, when that kind of work is done, there’s tremendous support. This bill will make it easier to have more of those interactions. Financial support for prescribed fire work is available; the real challenge now is these liability issues.

How do Native tribes that have done controlled burning for millennia figure into this?

Work remains to be done figuring out how to incorporate cultural burning into a claims fund process – it’s an unfinished aspect of this pilot. I would hope before we move toward a permanent solution, we solve that problem. And this is one of the things our Smoke Policy Lab will be working on this year, in partnership with the Karuk Tribe Department of Natural Resources. (Read more about the policy lab.)

What other major obstacles to prescribed burning remain? How can we overcome them?

The real limiter for doing prescribed burning in California is having trained personnel available and having backup units available. If CalFire doesn’t have resources to stand by, a burn won’t happen. If we’re going to change the fire ecology of the state – which is really what we need to do to keep communities safe – we need to train an army of people. It implies a huge investment in rural California and lots of jobs. We need as much emphasis on good fire as we currently have on fire suppression.

Why should Californians who don’t live near wildfire-prone areas care about this bill?

Anybody that lives in L.A. or the Bay Area or the San Joaquin or Central Valley over the past five years has experienced terrible air quality. Stanford scholarship from Kari Nadeau, Mary Prunicki, Marshall Burke, and Sam Heft-Neal has made this point in many different ways. Prescribed fire makes a little bit of smoke to avoid a very large volume of smoke. You can choose the day and weather conditions so the smoke doesn’t expose people in communities downwind. While our understanding of the impacts of wildfire smoke is developing rapidly, the more we are learning, the more serious the threat to public health seems to be.

Wara is also interim policy director for the Sustainability Accelerator at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

Source: Stanford

Do your part to prevent human caused wildfire: Part 5

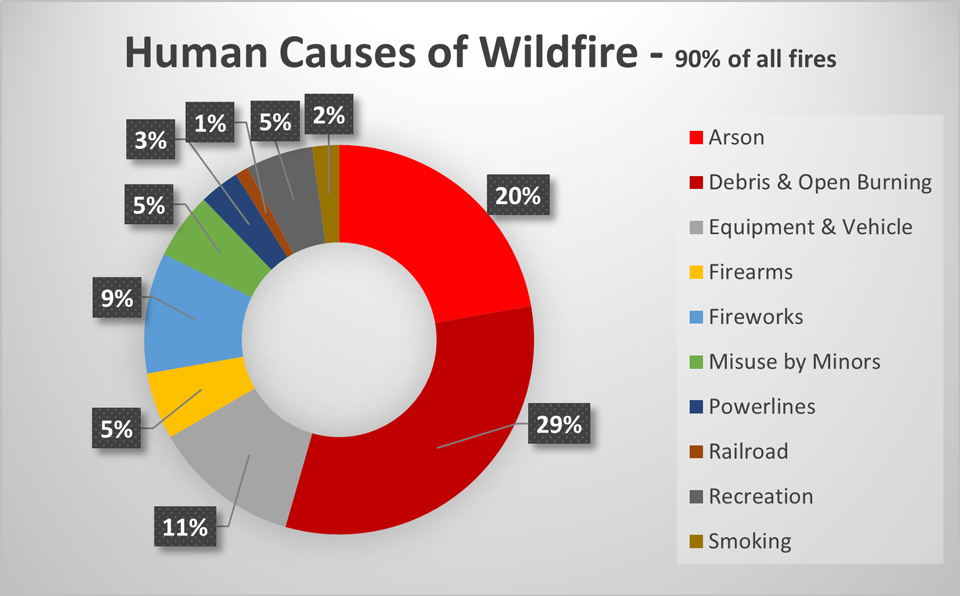

September 26, 2022 – By Michele Nowak-Sharkey, UC Master Gardener of Mariposa County – The largest natural cause of fire is lighting. However, most fires are human caused. The percentage varies from 89% – 95% depending on the source. With the increase in drought, fuel build-up in unburned forests, earlier springs, higher temperatures, beetle infested weakened trees, with the addition of a bit of wind and the same actions that might have easily extinguished a small fire in the past are now creating dangerous infernos.

September 26, 2022 – By Michele Nowak-Sharkey, UC Master Gardener of Mariposa County – The largest natural cause of fire is lighting. However, most fires are human caused. The percentage varies from 89% – 95% depending on the source. With the increase in drought, fuel build-up in unburned forests, earlier springs, higher temperatures, beetle infested weakened trees, with the addition of a bit of wind and the same actions that might have easily extinguished a small fire in the past are now creating dangerous infernos.

Being aware of our everyday choices can impact the number and magnitude of fires in the future.

(https://www.nifc.gov/fire-information/fire-prevention-education-mitigation/wildfire-investigation)

Debris and open burning include burn piles, yard debris, burn barrels, ditch/fence line burning, pest control, open trash burning, burning personal items, distress/signal fires, land clearing, right-of-way hazard reduction, or other escaped controlled burning. Windblown embers or fire creeping from the control burn area into un-cleared vegetation are the primary ignition mechanisms.

How to prevent: Landscape debris piles must be in 4 feet by 4 feet piles. Clear all flammable material and vegetation within 10 feet of the outer edge of pile.

Keep a water supply and shovel close by.

A responsible adult is required by law to be in attendance until the fire is out.

Stay mindful of current weather conditions when burning. If it’s windy and the surrounding vegetation is very dry, it may be best to wait and burn another day.

Check Mariposa County for burn permit requirements. 209 966-1200. (https://cemariposa.ucanr.edu/Fire_Information/Permits_and_Regulations/Mariposa_County_Permitting)

Arson is the criminal act of deliberately or maliciously setting fire to property including public lands with the intent to damage or defraud. Devices and “hot sets” are commonly used to ignite fires.

How to prevent: If you see or know of unusual activity in an area where wildfires are occurring, report it immediately. Note descriptions of vehicles and people in the area including dates, times, and location. Photos and videos are extremely helpful!

Equipment/Vehicle fires range from heavy construction to small portable engines (passenger vehicles/RVs, motorcycles, OHV, ATV, trailers, road graders, bulldozers, tractor trailers, welders, grinders, wind generators, chain saws, pumps, generators, etc.).

Ignitions sources are mechanical breakdowns/malfunctions such as exhaust (direct heat transfer, organic material collecting on the exhaust system, and particles), catalytic converter pieces, hot metal fragments, metal/pavement contact (dragging trailer chains and metal parts), friction, flat tires, spark arrestor malfunctions, faulty electrical system/wiring, collisions, refueling operations, and rock/hard surface strikes.

How to Prevent: Perform regular maintenance on your vehicles – secure chains, inspect for dragging parts, check tire pressure, and properly maintain brakes. Visit Ready for Wildfire equipment use for more prevention tips. (https://www.readyforwildfire.org/prevent-wildfire/equipment-use)

Firearms and explosives use requires being aware of any firearm projectiles along with flares from flare guns and signal flares.

How to Prevent: Explosives, exploding targets, incendiary ammunition and tracer bullets are prohibited on public lands during high fire danger. Check for fire restrictions and prohibited uses in the area. To prevent wildfires while target shooting, follow these tips:

Bring a shovel and water or fire extinguisher.

Place your targets on dirt or gravel, clear and away from grass and other vegetation.

If fire danger is high (dry, hot, and windy) consider shooting at an established outdoor or indoor range.

Know your ammunition – don’t shoot steel component, tracer, or incendiary bullets.

Bullets can spark when striking solid objects, sending hot fragments into vegetation – don’t shoot trash like TVs and appliances or at rocks and metal targets such as signs.

Fireworks burn at extremely elevated temperatures making all fireworks ignition sources especially the airborne type (i.e., bottle rockets and roman candles). Even sparklers burn at 1200°F.

How to prevent: Despite the dangers of fireworks, few people understand the associated risks – devastating burns, other injuries, fires, and even death. During times of high fire danger, federal and local agencies impose fire restrictions and/or fire prevention orders.

Misuse of fire by minors has its own category. Young children, ages 12 or younger, motivated by normal curiosity may use fire in an experimental fashion; “playing with matches.” They look for easily accessible ignition devices and frequently use both paper and wood matches, lighters, fireworks, or magnifying glasses to ignite fires.

How to prevent: Set a good example and teach children fire safety at an early age. The most critical message for children to learn is that matches, and lighters are tools and not toys! Parents should never use lighters, matches and fire for fun – children will mimic the behavior,

Power line caused wildfires are often due to high winds, contact with vegetation, equipment failure, or human or animal contact with a power line (conductor wire). Several of these factors may work to cause a fire, such as wind blowing vegetation into contact with the electrical equipment.

How to prevent: Proper maintenance including vegetation clearance around equipment can help prevent wildfires. For your safety, however, stay away from power lines, meters, transformers, and electrical boxes. Leave the maintenance to the professionals – if you see vegetation close or in contact with power lines or bird nest close to the lines or conductor boxes, notify your utility company.

Recreation and ceremony include campfires improperly constructed, unattended, improperly extinguished, or abandoned; barbeque/smokers; bonfires; ceremonial fires; gas cookers, warming and lighting devices; luminary (sky lanterns); and outdoor fireplaces, metal fire rings and candles.

How to Prevent: Learn how to construct a proper campfire and how to put it out. (https://smokeybear.com/en/prevention-how-tos/campfire-safety) Never leave grills and smokers unattended. Watch weather conditions closely when considering have a bonfire, ceremonial fire or using candles.

Smoking fires are generated from discarded unextinguished cigarettes and other materials used for smoking. Wildfires caused by smoking activities or accoutrements, include matches, cigarettes, cigars, pipes, electronic cigarettes (vape heads), and drug paraphernalia.

How to Prevent: Never flick cigarette butts out the window. Watch where you toss used matches and other smoking accoutrements. Beware of wind conditions when using such paraphernalia.

We want to get back to fire as a beneficial effect on the landscape rather than a damaging effect.

As Smokey says “Only YOU can help prevent wildfires” by our personal actions and the actions we take as a community.

Next Up: Defensible Space and How to Create It

Related:

Over the Garden Fence – The Partnership Between Humans and Nature During Fire Recovery: Part 4

Over the Garden Fence – The Partnership Between Humans and Nature During Fire Recovery: Part 3

Over the Garden Fence – The Partnership Between Humans and Nature During Fire Recovery: Part 2

Over the Garden Fence – The Partnership Between Humans and Nature During Fire Recovery

For assistance, contact our Helpline at (209) 966-7078 or at mgmariposa@ucdavis.edu. We are currently unable to take samples or meet with you in person but welcome pictures.

The U.C. Master Gardener Helpline is staffed; Tuesdays from 9:00 A.M. – 12:00 P.M. and Thursdays from 2:00 P.M. – 5:00 P.M.

Clients may bring samples to the Agricultural Extension Office located at the Mariposa Fairgrounds, but the Master Gardener office is not open to the public. We will not be doing home visits this year due to UCANR restrictions.

Serving Mariposa County, including Greeley Hill, Coulterville, and Don Pedro

Please contact the helpline, or leave a message by phone at: (209) 966-7078

By email (send photos and questions for researched answers) to: mgmariposa@ucdavis.edu

For further gardening information and event announcements, please visit: UCMG website: https://cemariposa.ucanr.edu/Master_Gardener

Follow us on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/mariposamastergardeners

Master Gardener Office Location:

UC Cooperative Extension Office,

5009 Fairgrounds Road

Mariposa, CA 95338

Phone: (209) 966-2417

Email: mgmariposa@ucdavis.edu

Website: http://cemariposa.ucanr.edu/Master_Gardener

Visit the YouTube channel at UCCE Mariposa.

Scorched Earth – Soil Rx

September 1, 2022 – Tery Susman, UC Master Gardener of Mariposa County – Wildfires can create immediate and potentially long-term soil erosion. However, there are a number of ways to mitigate this  post-fire concern.

post-fire concern.

Adapted from the California Native Plant Society Fire Recovery Guide: https://www.cnps.org/give/priority-initiatives/fire-recovery.

If a fire has burned so severely that no material is left on the ground, patches of soil form a crust and become hydroponic (water repellent), increasing runoff. This might necessitate applying chips, mulch from dead debris or straw.

Spreading mulch is the most effective erosion control treatment because it provides what the fire and heavy equipment removed – ground cover! This ground cover allows water to infiltrate the soil instead of running off and eroding it.

Prune or remove only high hazard fire-damaged trees near buildings and roads. Keep felled trees and pruning on-site. These trees can be a source of mulch.

Spread: a mulch application. Straw mulch has high efficacy in reducing rainwater runoff, soil erosion, and downstream sedimentation. Use loose barley or wheat straw because it is longer lasting. Rice straw is less expensive. Use when the straw doesn’t need to last as long. Use straw mulch in “free form”, no more than 2-3 inches deep. Mulch in 6-10 foot strips along contour, spaced at 50-100 foot intervals, depending on the steepness of the slope.

Use wood mulch from local materials, including burned trees, shredded debris, or thinned, unburned trees ,wattles, mulch, rocks, and branches can slow down and disperse the runoff, limiting erosion and sediment.

Use straw wattles to shorten slope length. They are designed for short slopes or slopes flatter than 3:1 and low surface flows. For more information on the proper wattle installation go to: https://ucanr.edu/sites/postfire/files/247999.pdf.

Sink: Place rocks, gravel, or crushed rock in areas of high traffic.

Share: Work with neighbors to create a plan to slow runoff. In disturbed areas of moderate to high fire intensity, a neighborhood plan can be critical in preventing sediment and fire debris from washing into sensitive creek habitats and contributing to flooding.

Natural Resources Conservation Services – www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/site/ca/home, call (209) 966-3431

CAL Fire – www.fire.ca.gov (209) 966-3622

Recovering from a wildfire can be a daunting process. Be patient with yourself and with nature. Do what you can, ask for help, and know that our community is STRONG!

Next: Give Trees a Chance – Ecosystem Resilience

Photo Credit: Maxwell Rygiol, from 2017 Detwiler Fire

Photo Credit: Maxwell Rygiol, from 2017 Detwiler Fire

For assistance, contact our Helpline at (209) 966-7078 or at mgmariposa@ucdavis.edu. We are currently unable to take samples or meet with you in person but welcome pictures.

The U.C. Master Gardener Helpline is staffed; Tuesdays from 9:00 A.M. – 12:00 P.M. and Thursdays from 2:00 P.M. – 5:00 P.M.

Clients may bring samples to the Agricultural Extension Office located at the Mariposa Fairgrounds, but the Master Gardener office is not open to the public. We will not be doing home visits this year due to UCANR restrictions.

Serving Mariposa County, including Greeley Hill, Coulterville, and Don Pedro

Please contact the helpline, or leave a message by phone at: (209) 966-7078

By email (send photos and questions for researched answers) to: mgmariposa@ucdavis.edu

For further gardening information and event announcements, please visit: UCMG website: https://cemariposa.ucanr.edu/Master_Gardener

Follow us on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/mariposamastergardeners

Master Gardener Office Location:

UC Cooperative Extension Office,

5009 Fairgrounds Road

Mariposa, CA 95338

Phone: (209) 966-2417

Email: mgmariposa@ucdavis.edu

Website: http://cemariposa.ucanr.edu/Master_Gardener

Visit the YouTube channel at UCCE Mariposa.