October 16, 2022 – By Meghan Snow – Seeing a forest recently burned in a wildfire can be jarring. Green is replaced by shades of gray. The land is quiet. The sunshine feels hotter. However, it’s not long before the forest comes back to life.

“Wildlife is incredibly resilient,” said Stephanie Eyes, a senior wildlife biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Sacramento Fish and Wildlife Office. “California has a long history with wildfire, and many species adapted to endure it.”

Eyes has evaluated the impacts of wildfire on wildlife for more than a decade. Before joining the Service, she worked for Yosemite National Park, surveying the impacts of fire on California spotted owl. Today, she uses data collected on wildfires to determine the impact on habitat for endangered, threatened and at-risk species living in the Sierra Nevada.

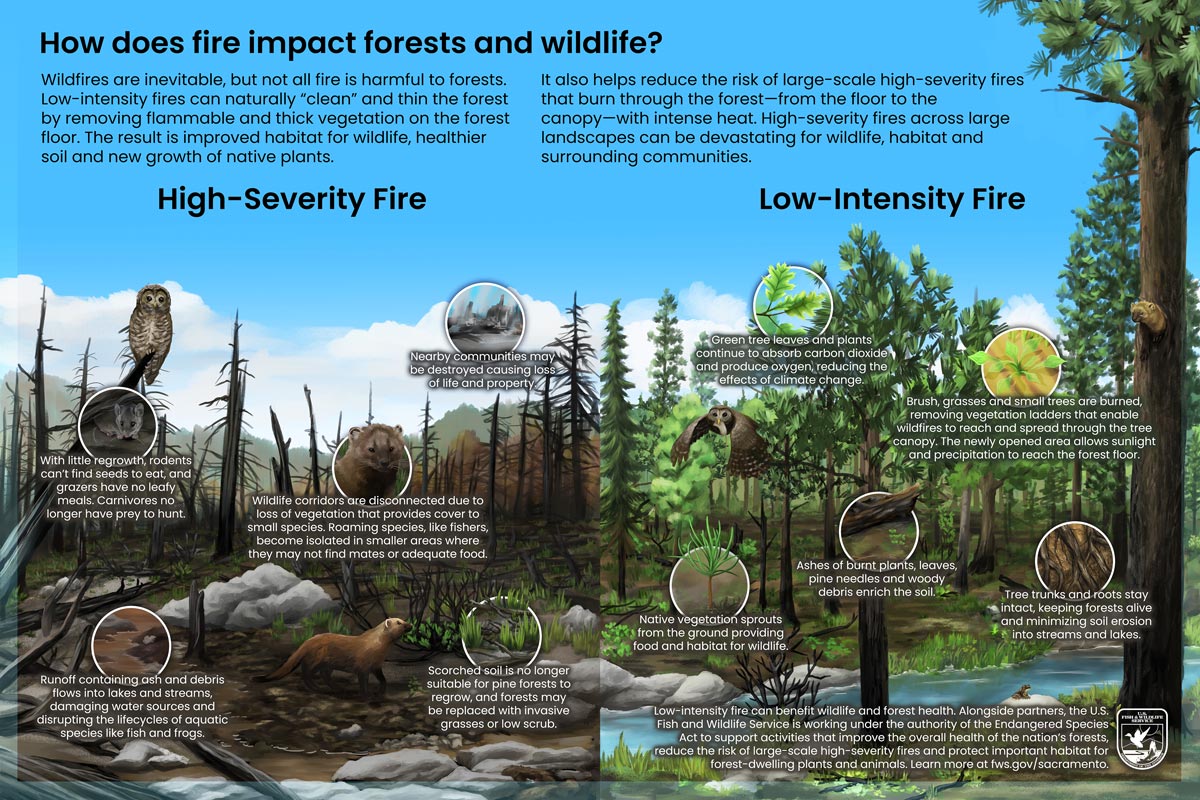

Fires burn at different heat levels, can be large or small, and cause varying impacts on the land, wildlife, and nearby communities. Topography, the amount of dry vegetation present and weather factor into how large and damaging the fire becomes. Low-intensity fires burn close to the ground, “cleaning” and thinning the forest by removing thick and flammable vegetation from the forest floor. High-severity fires burn with high heat, climb into and remove the tree canopy, and can scorch the soil and tree roots. At a large scale, high-severity fires can be incredibly damaging to wildlife and the ecosystem. Mosaic fires are a mix of mostly low-intensity fire with patches of high- and moderate-severity fire and some unburned forest. Wildlife can survive, and even thrive, in areas that experience mosaic fires.

When wildfires erupt, animals do their best to move out of the direct path of the flames while staying close to home if they can find safe refuge.

“Wildlife will move around their home area, avoiding the smoke and actively burning areas until it’s safe to return,” explained Eyes.

Some animals, like frogs and rodents, don’t move far. They’ll retreat into deep underground burrows where they are protected from the heat. Fish and frogs will swim to the deepest parts of their stream or lake. If the fire is burning just a few feet high, birds and animals that can climb will sometimes go up into the branches and tree canopy to avoid the flames. Fishers may crawl into a tree cavity for protection. Other animals, like deer and bears, will move around the forest until the flames subside.

“When I was working in Yosemite, there was a female California spotted owl who weathered several wildfires. We were always concerned about her, but she would still be there, year-after-year,” said Eyes.

But when a high-severity fire burns across a large landscape, it moves fast and climbs through the tree canopy. Wildlife has a more challenging time finding refuge from these flames.

“Wildlife have adapted to deal with smaller fires, and unfortunately, sometimes they can’t escape these recent, big fires,” said Eyes.

The Service listed the southern Sierra Nevada fisher in 2019 and the Sierra Nevada red fox in 2021, both as endangered species. High-severity wildfires were identified among the leading threats to the ongoing survival of both species due to loss of habitat and elimination of safe movement corridors. As climate change prolongs periods of drought, forests and the species that live there will continue to face the threat of large, high-severity wildfires.

AFTER THE BURN

Over the past seven years, high-severity wildfires burned thousands of acres across California. Unprecedented drought mixed with mid-summer lightning storms ignited wildfires so large they created their own weather systems. While many areas burned severely, pockets of forest continue to thrive.

Nancy Kelly, a wildlife biologist for the U.S. Forest Service’s Sequoia National Forest, has worked for more than 20 years surveying and studying wildlife habitat.

“The adaptability of wildlife continues to surprise me,” said Kelly. “They can make do with what’s left after a fire.”

As a wildlife biologist, Kelly advises staff at Sequoia National Forest on ways to reduce the impact of management activities, such as prescribed burns and tree thinning projects, on endangered, threatened and at-risk species.

“Initially, fire is a big deal. It changes how species interact with their habitat for a long time,” said Kelly. “But fire is a tool that nature has been using for eons to keep ecosystems intact.”

After low-intensity fires, grasses and ferns are the first to come back, aided by newly enriched soil from the ashes of burned leaves, plants, and woody debris, as well as sunlight that can now reach the forest floor. Trees are still alive and sprout new leaves during the next growing season. Their intact root systems prevent soil from eroding into nearby streams and lakes.

“We have seen populations of sensitive plants double after a fire because they like the open canopy,” said Kelly.

It doesn’t take long for wildlife to start using low-intensity burn areas. New grasses, ferns and fallen branches provide just enough coverage for mice and squirrels to feel safe as they scavenge for seeds dropped during the fire. Their presence attracts owls, fishers, foxes and other animals that take advantage of newly opened areas on the forest floor to spot prey. Tender grass shoots provide food for herbivores like deer and rabbits. Amphibians scramble back to their waterfront homes to feast on insects that have also returned.

“We will see wildlife come back through the area as it cools back down,” said Kelly. “They’re curious like we are. They take advantage of the new growth and other food sources that are available after the burn.”

Regrowth after a large-scale, high-severity fire looks different. Some of the soil is scorched to a degree that tree roots underneath the surface are burned, killing the tree. Ash from leaves and woody debris may take longer to breakdown and enrich the soil to a point that vegetation can sprout from the ground. Rain can often cause the soil to erode into nearby waterways. Muddy waters result in less clean water sources for animals to drink from and can also bury amphibian and fish eggs before they hatch.

“While these high-severity burn areas look like moonscapes, they are not completely devoid of life. It’s just different life,” explained Kelly.

Woodboring beetles start colonizing the freshly burnt trees. Woodpeckers move in to eat the beetles. The dead trees fall, their ash providing much needed nutrients to restore the soil.

“Unfortunately, in some of these large, high-severity burns, we’re seeing more invasive grasses and weeds grow because they can survive in less ideal conditions,” said Kelly. “These species can outcompete native grasses and plants for water and light.”

One native plant, mountain white thorn, grows low to the ground when forest canopies are present. But after a high-severity fire, the shrub can regrow to heights over 6 feet. Their growth then blocks sunlight to tree seedlings sprouting from the ground, and the landscape can transition from forestland to scrubland.

Kelly explained that sometimes the animal life after a fire transitions, too.

“This year, we’ve seen red-tailed hawks and other grassland bird species because we have more open area now,” she said. “Until trees come back, I expect that we’ll continue to see these grassland and open area species in the mountains.”

TO STAY OR GO

More than 100 years could pass before large trees return to the landscape after a high-severity fire, and some species can’t survive without the forest canopy, even if they try.

“California spotted owls can find places to perch, but they can’t find good places for nesting,” said Eyes. “Just like us, if they don’t have a roof over their heads, they’ll leave.”

Fishers also avoid the open landscapes, which leave them vulnerable to predators as they move between their dens and scavenging grounds. Fishers often travel miles looking for food, mates and good reproductive habitat, but high-severity wildfires can often cut off those safe travel corridors, restricting them to smaller and smaller ranges and reducing their chances of finding a mate and enough prey.

Luckily, agencies like the U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management work to restore habitat after large fires like these.

“If a prescribed burn can be used to reduce the risk of a high-severity fire or vegetation can be planted immediately after the fire, the wildlife will typically come back,” said Eyes.

The Sequoia National Forest conducts a variety of activities aimed at reducing the risk of large-scale, high-severity fire, such as prescribed burns, brush management projects and thinning overgrown groves of trees. Kelly works with biologists at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to determine ways to minimize the impact on listed species in the area. While the projects cause some minor disruption while they’re taking place, the period is usually short and much less disruptive and damaging than a high-severity fire.

Kelly and her team also support the restoration of burned landscapes by replanting native vegetation and trees on open slopes and near streams to reduce erosion and jump start the process of bringing the area back to life.

“The forests provide the food, water and shelter for wildlife, but they’re also important to humans,” said Kelly. “By taking care of the forests, we’re also taking care of our air, water sources and communities.”

Source: USFWS