To Seed or Not to Seed? – The best approach to revegetation

September 23, 2022 – Tery Susman, UC Master Gardener of Mariposa County – To seed or not to seed…that truly is the question.

Adapted from the California Native Plant Society Fire Recovery Guide:

Adapted from the California Native Plant Society Fire Recovery Guide:

https://cnps.org/gove/priority-initiatives/fire-recovery

ANR Publication 8366 – Recovering from Wildfire: a Guide for California’s Forest Landowners: https://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu/Details.aspx?itemNo=8386

Our human tendency is to fix what we perceive as a potential problem or as something “broken” or “untidy”. Our first thought is to reseed flowering plants and grasses on our fire scorched property to speed up vegetation establishment and soil stability; fixing what is “broken”. However, recent research has shown that seeding is not more effective than letting the area recover naturally; and given the risk of introducing invasive species, it is generally no longer recommended.

Natural regeneration gives the land a chance to recover on its own from the existing soil seed bank, nearby seed sources, and the resprouting of surviving perennial plants.

The research indicates two important points regarding reseeding grasses following wildfire:

- This management practice is usually not cost-effective

- It appears to create more problems than it solves

Potential negative effects of this practice include:

- Seeds of invasive annual grasses like wild oats, ryegrass, and bromes develop shallow root systems that have little to no effect on slope stability

- Seeding provides marginal effects/results in the first year following fire or not at all and no significant effect when slower native perennials are the plant of choice in the first year

- Seeding uses up more ground moisture and reduces regrowth of native plants that regenerate from resident seed bank in the soil

- Native grass seeding may cause gene pollution of resident native grasses especially if the grasses sowed were of a different gene type and collected in other areas of the state

- Seeding may have long-term negative effects on the ecosystem by changing plant community composition over time

- Seeding can attract pocket gophers leading to more opportunities for soil piping, a situation in which runoff and/or water-saturated soil enters gopher holes and erodes the soil below the ground

- Seedbed preparation can cause disturbance to slopes, soil, pre-existing vegetation, and the surrounding seedbank

- Seeding can give property owners a false sense of security that this one practice will mitigate most post-fire land issues

Seeding is no longer the recommended practice following a wildfire. However, many experts also agree that for specific erosion control problems, it may be necessary to seed native perennial grass to mitigate these issues.

Potential positive effects of seeding grasses:

- Native or sterile non-native grasses can reduce non-native invasive plant encroachment by competition

- Seeding can increase infiltration and reduce surface runoff and resulting soil erosion

- Seeding may be used purposely to reduce shrub regrowth on range and pasture lands

Before you decide to plant grass seed on wildfire damaged soil and slopes, reach out to Natural Resources Conservation Services (NCRS) for a site-specific evaluation of your post- fire property needs:

Natural Resources Conservation Services – (209) 966-3431 www.nrcs.usda.gov.wps.portal.nrcs/site/ca/home

There are distinct reasons that may be addressed by seeding, but in general natural regeneration is the best option. Remember, lands have recovered many times after wildfires. Once human-made debris is removed, in most cases the land will heal on its own. It just takes time!

To seed or not to seed? In most cases the answer is not to seed. Next: YOU can help prevent wildfire spread.

Related:

Over the Garden Fence – The Partnership Between Humans and Nature During Fire Recovery: Part 3

Over the Garden Fence – The Partnership Between Humans and Nature During Fire Recovery: Part 2

Over the Garden Fence – The Partnership Between Humans and Nature During Fire Recovery

For assistance, contact our Helpline at (209) 966-7078 or at mgmariposa@ucdavis.edu. We are currently unable to take samples or meet with you in person but welcome pictures.

The U.C. Master Gardener Helpline is staffed; Tuesdays from 9:00 A.M. – 12:00 P.M. and Thursdays from 2:00 P.M. – 5:00 P.M.

Clients may bring samples to the Agricultural Extension Office located at the Mariposa Fairgrounds, but the Master Gardener office is not open to the public. We will not be doing home visits this year due to UCANR restrictions.

Serving Mariposa County, including Greeley Hill, Coulterville, and Don Pedro

Please contact the helpline, or leave a message by phone at: (209) 966-7078

By email (send photos and questions for researched answers) to: mgmariposa@ucdavis.edu

For further gardening information and event announcements, please visit: UCMG website: https://cemariposa.ucanr.edu/Master_Gardener

Follow us on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/mariposamastergardeners

Master Gardener Office Location:

UC Cooperative Extension Office,

5009 Fairgrounds Road

Mariposa, CA 95338

Phone: (209) 966-2417

Email: mgmariposa@ucdavis.edu

Website: http://cemariposa.ucanr.edu/Master_Gardener

Visit the YouTube channel at UCCE Mariposa.

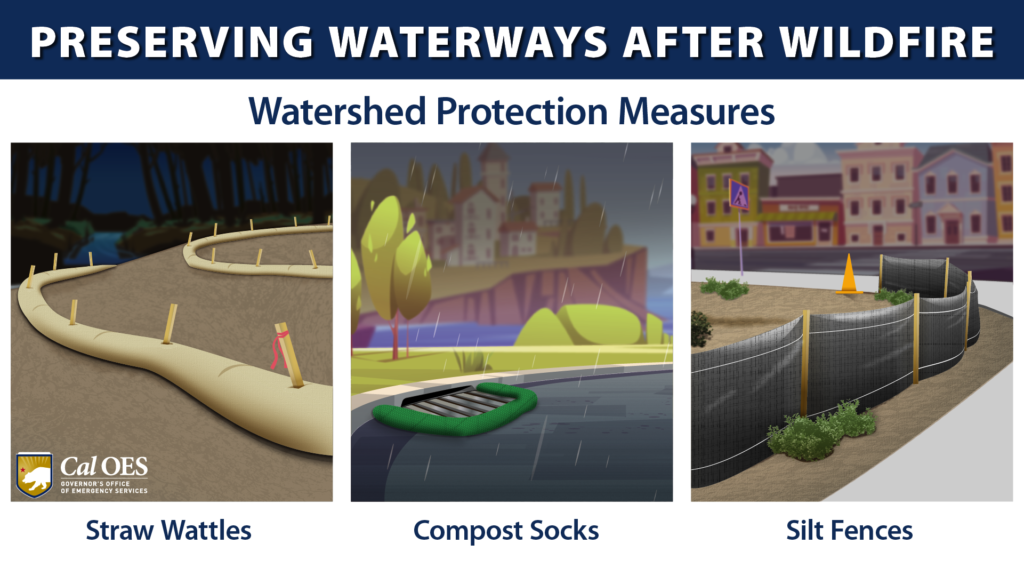

Cal OES works closely with state partners to prevent toxic runoff from entering waterways by installing physical filtration barriers. The placement of these emergency protective measures helps safeguard watersheds from the potential impacts of dangerous toxins found in wildfire ash and debris. By intercepting water flow from slopes, the barriers act as filters to remove dangerous contaminants before they can pollute the waterway.

Cal OES works closely with state partners to prevent toxic runoff from entering waterways by installing physical filtration barriers. The placement of these emergency protective measures helps safeguard watersheds from the potential impacts of dangerous toxins found in wildfire ash and debris. By intercepting water flow from slopes, the barriers act as filters to remove dangerous contaminants before they can pollute the waterway.