Give Trees a Chance-Ecosystem Resilience

September 13, 2022 – By Michele Nowak-Sharkey, UC Master Gardener of Mariposa County – The impulse after a fire is to remove all evidence that the event occurred. This is  understandable from an emotional perspective, however if we shift to the nature lens, we see a different approach.

understandable from an emotional perspective, however if we shift to the nature lens, we see a different approach.

Although the landscape looks blackened with no visible signs of life, life nonetheless is rearranging, communicating, and developing a plan as it shakes off the fire trauma.

Trees have a huge impact on ecosystem recovery. Trees contribute by providing oxygen, improving air quality, climate amelioration, conserving water, preserving soil, and supporting wildlife. To say nothing of the joy we humans experience when we interact with our leafed friends through recreation, food gathering or simply viewing.

Structurally unsound trees that threaten buildings and roads need to be felled. However, it is advised to wait 1- 3 years after a fire to determine if a tree will recover, especially larger, more valuable trees. In wildfire recovery, we need to Give Trees A Chance.

Identify: Know your trees. Mariposa County has a diverse mix of pine species, oak varieties, plus firs, manzanita, buckeyes, sycamores and more.

Knowing tree types supplies information about their coping mechanisms with fire, possibility of when they will bring on new leaves/needles, if they will re-sprout from the crown/base of the tree or have seeds that will sprout following a fire.

Other factors that impact tree survival include growth stage at the time of fire, how close together trees were, the chemical and physical characteristics – oil/wax content, vegetation underneath, the season and drought conditions.

Sources for tree identification: http://bit.ly/ucanroaks & https://www.calflora.org. There are also phone apps that can assist too.

Appraise: Leaf/needle scorch, root/trunk/branch damage, cambium (the inner layer between the bark and the wood) injury and bud death are signs of fire damage. These factors alone don’t indicate a tree is dead. A tree with blackened bark might look unsavable. The Ponderosa pine, as it matures, develops a thicker bark that is more fire-resistant. If the bark hasn’t been completely burned off the trunk, exposing the cambium, the tree may survive.

With blackened trees cut a quarter-sized piece, one-half inch through the bark. If you see a green or white moist cambial layer right below the bark, the tree will probably recuperate. Check burned branches- peel back a bit of bark. If there is a thin white/green layer those twigs/branches may be alive.

Look for burned roots around the base and several feet away. Roots are 6-8 inches below the surface. Gently unearth roots in a few locations. If they are supple, not

brittle/dried out, survival is good. If 50% of the roots are burned, the tree is unstable.

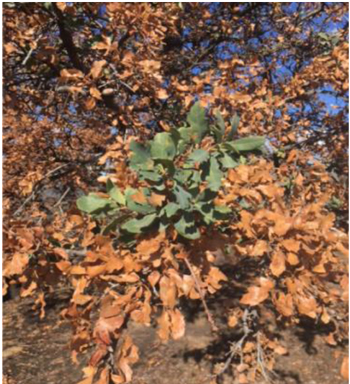

Burned leaves/needles might be attached to a live tree. New leaves may sprout from the crown/base of the tree. As witnessed in this picture of an oak from the Telegraph fire, the leaves over most of the tree were scorched but within a year, new green leaves sprouted.

Telegraph Fire 2008 – photo credit, Kris Randal (pictured right)

Telegraph Fire 2008 – photo credit, Kris Randal (pictured right)

It is important to look for buds. If they are green and moist, not dry, and brittle or twigs bend easily, survival is good.

https://anrcatalog.uncanr.edu Publication 8386

https://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu Publication 8445

https://cemariposa.ucanr.edu/Fire_Information/Post-fire_Restoration/Landscape_Restoration_685

Support: Water trees once the scorched crust layer on soil is cared for. Slowly soak the entire area under the dripline and beyond a few feet to a depth of 12 inches. Do not water the trunk just the surrounding area. Check trees weekly. Water when the soil dries to 6 inches deep.

Protect trunks and large limbs from sunburn until leaf/needles regrow. Loosely wrap in permeable light-colored cloth or cardboard. During fall, prune dead, broken limbs.

https://naes.agnt.unr.edu/PMS/Pubs/1510_2004_96.pdf

Watch: Kris Randal, UC Master Gardener, CA Naturalist/Oak Specialist says dead trees have value too! More than 80 species of birds rely on dead trees for nesting and food. Acorn woodpeckers establish large granaries in dead oaks and conifers. Insects, fungi and more than 300 different types of wildlife rely on dead trees also. Consider leaving a few standing dead trees if they don’t present a hazard.

Spend the first year after fire watching as life surfaces once more. Be a patient partner, give trees AND nature a chance.

Next: To Seed or Not to Seed

Related:

Over the Garden Fence – The Partnership Between Humans and Nature During Fire Recovery: Part 2

Over the Garden Fence – The Partnership Between Humans and Nature During Fire Recovery

For assistance, contact our Helpline at (209) 966-7078 or at mgmariposa@ucdavis.edu. We are currently unable to take samples or meet with you in person but welcome pictures.

The U.C. Master Gardener Helpline is staffed; Tuesdays from 9:00 A.M. – 12:00 P.M. and Thursdays from 2:00 P.M. – 5:00 P.M.

Clients may bring samples to the Agricultural Extension Office located at the Mariposa Fairgrounds, but the Master Gardener office is not open to the public. We will not be doing home visits this year due to UCANR restrictions.

Serving Mariposa County, including Greeley Hill, Coulterville, and Don Pedro

Please contact the helpline, or leave a message by phone at: (209) 966-7078

By email (send photos and questions for researched answers) to: mgmariposa@ucdavis.edu

For further gardening information and event announcements, please visit: UCMG website: https://cemariposa.ucanr.edu/Master_Gardener

Follow us on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/mariposamastergardeners

Master Gardener Office Location:

UC Cooperative Extension Office,

5009 Fairgrounds Road

Mariposa, CA 95338

Phone: (209) 966-2417

Email: mgmariposa@ucdavis.edu

Website: http://cemariposa.ucanr.edu/Master_Gardener

Visit the YouTube channel at UCCE Mariposa.

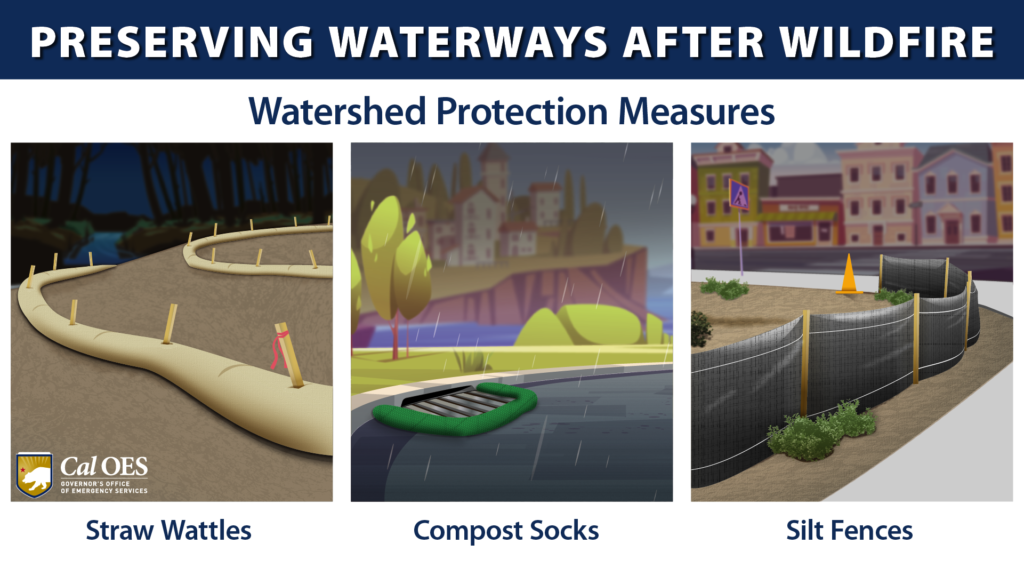

Cal OES works closely with state partners to prevent toxic runoff from entering waterways by installing physical filtration barriers. The placement of these emergency protective measures helps safeguard watersheds from the potential impacts of dangerous toxins found in wildfire ash and debris. By intercepting water flow from slopes, the barriers act as filters to remove dangerous contaminants before they can pollute the waterway.

Cal OES works closely with state partners to prevent toxic runoff from entering waterways by installing physical filtration barriers. The placement of these emergency protective measures helps safeguard watersheds from the potential impacts of dangerous toxins found in wildfire ash and debris. By intercepting water flow from slopes, the barriers act as filters to remove dangerous contaminants before they can pollute the waterway.